1-pager: West Side Story

Background & Creators

Classically-trained choreographer Jerome Robbins had started talking to the accomplished American composer Leonard Bernstein in the mid 1950’s about doing a modern version of Romeo and Juliet in the Broadway musical style. Initially Robbins was thinking about immigrant Jews on the lower East Side, where he was born and raised. Through various metamorphoses it changed into a rivalry between American and Puerto Rican gangs—much more in the news at the time—in the Hell’s Kitchen area of Manhattan, ironically the very neighborhood where Lincoln Center would soon be built as part of an urban-renewal project. Playwright Arthur Laurents would write the book (script or libretto) and Bernstein would write the music and lyrics (though Stephen Sondheim got involved later to rescue the lyrics). Robbins would “conceive, direct and choreograph” the whole piece, as he would repeat later with Gypsy (on which he would again work with Laurents and Sondheim) and Fiddler on the Roof, paving the way for other director-choreographers such as Bob Fosse (Pippin, Chicago) and Michael Bennett (Follies, A Chorus Line). Hal Prince, an ambitious 29-year-old producer who wanted to get into directing, was lined up to produce the show.

When it opened in 1957, West Side Story was the first Broadway musical to both show and suggest violence onstage. There are choreographed gang fights involving knives, chains and rocks; the suggestion of possible gang rape of Anita; and the death of the major characters rather than a happy ending. This dark element may have been responsible for the lukewarm critical reception the show received; the leading contender for that year’s Best Musical was The Music Man, a traditional, upbeat, happy-ending Broadway musical following proven formulas. Reviews were mixed, criticizing both the production and the material. Given that the next “dark” musical wouldn’t emerge for 10 years (Cabaret, 1967), WSS was ahead of its time thematically.

Lyrics

Bernstein had recently been introduced to 27-year-old Stephen Sondheim at a salon, and was persuaded to take him on as co-lyricist. Sondheim really wanted to write his own music and lyrics, but his mentor and adopted father figure Oscar Hammerstein II (then already working with Richard Rodgers and a huge commercial success) advised Sondheim to seize the opportunity to work with such accomplished professionals and “break into” commercial musicals.

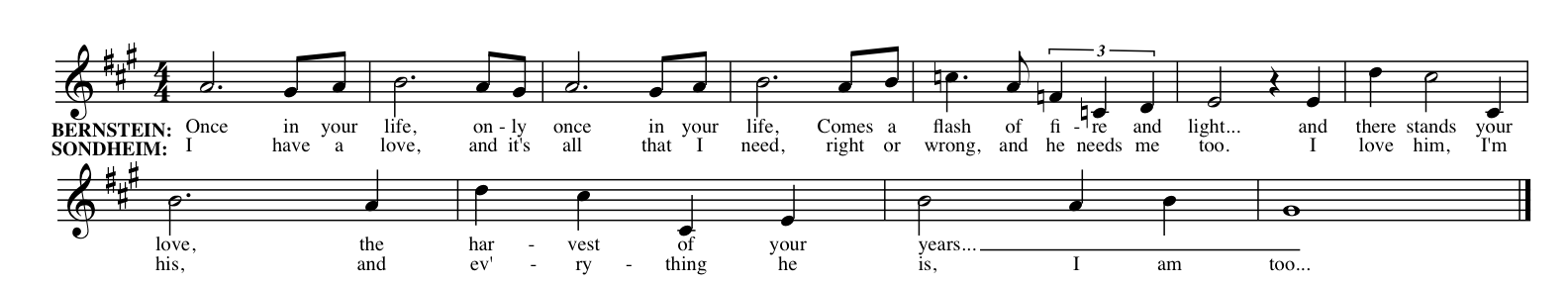

In truth, Bernstein’s lyrics were awful. His “purple” writing was reminiscent of bad poetry, and it was Sondheim’s smart, sharp lyrics that gave the songs the energy and character they needed. Below is an excerpt from Maria & Anita’s duet “I Have A Love” showing Bernstein’s original lyrics and Sondheim’s rewrite—which words are more likely to be spoken by a pair of relatively uneducated Puerto Rican immigrant sisters? Although Sondheim publicly beats himself up over some gaffes in the lyrics (such as when Maria sings “It’s alarming how charming I feel”), his work so completely transformed the lyrics that Bernstein ultimately gave Sondheim sole lyricist credit—a huge break for a relatively unknown artist.

Thirteen years after West Side Story, Sondheim and Prince would collaborate as composer and director on the landmark musical Company (1970), the first of many collaborations between them that would revolutionize Broadway.

Dance

While all musicals rely on both the book (dialogue) and song lyrics to tell the story, WSS is highly unusual in that the show doesn’t work unless all elements—book, music, lyrics, and dance—are well executed. The dances move the story along, rather than being ornamental; the music is itself a character in the show and its motivic construction keeps bringing us back to the show’s center of gravity (see below). The technical difficulty of executing and melding the music, lyrics and dance make WSS one of the most demanding shows to produce.

Jerome Robbins’s choreography makes the show unique (and indeed, it’s one of the few shows where revival productions hew closely to the original choreography, out of homage to the influence of its creator). Like Agnes deMille before him, who pioneered the use of balletic dance to help tell the story in a Broadway musical (the Dream Ballet sequence of Oklahoma!, 1943), Robbins brought his classical and modern dance training to WSS. At the opening of the show, we see the rival gangs, the Sharks and the Jets, strutting about their territory using sweeping arm gestures suggesting their “ownership” of their turf and dancing stylized combat sequences that radiate energy and violence despite their obvious artistry. Indeed, the opening sequence originally consisted of dialogue and a song (“My Greatest Day”), all of which was scrapped because Arthur Laurents thought the gangs’ attitudes and interactions with each other could be told more concisely and vigorously with just music and dance.

Music

The action of WSS is accompanied by a symphonic, Latin/jazz flavored score that is itself a character in the show, and is still unique in the history of musical theater. Most Broadway scores start out as simple, straightforward songs delivered by the composer, which are then “embellished” via orchestration. In contrast, not only are the songs in WSS constructed from unusual motivic elements, but the orchestration is itself a central and sophisticated element of the songs, such that you can’t “de-orchestrate” the songs without destroying their character. Bernstein had taken this approach—letting the orchestra function as a character in the show—in the earlier musical On The Town (1944), which captured a 24-hour shore-leave period of soldiers involved in WW2 and gave us the wistful ballad Some Other Time and the jaunty New York, New York, A Helluva Town. Bernstein himself closely supervised the orchestration, which was mostly executed by Sid Ramin and Phil Lang; Bernstein is one of the very few composers of a musical who is capable of doing so at a level of fine detail and in a symphonic style, where timbral and textural properties of the instruments contribute important elements to the score, as opposed to a “show style”, where a simple obvious melody line is accompanied by orchestration.

Thematically, the key structural element in the whole WSS score is a musical interval called a tritone, so called because it is the interval you get if you start on one note, and take three whole-steps up; for example, it’s the interval between the notes C and F#, or between F and B. The tritone recurs throughout the score, both melodically (the opening fanfare, the “Jet Song”, “Cool”, and “Maria”) and harmonically (e.g. in the closing chord of the show).

Musically, the tritone is interesting for two reasons. FIrst, it lies exactly halfway between a note and its octave; that is, the number of steps between C and F# is the same as the number of steps between F# and the next higher C. (See below.) This means that if you “invert” the interval by putting the bottom note on top, it’s still a tritone. No other musical interval has this property. Second, since it’s a dissonant (unstable) interval, your ear “wants” to hear the tritone “resolve” to a stable harmony, but unlike other dissonant intervals that suggest a single obvious resolution, the tritone can resolve equally well in two completely different ways, making it aurally ambiguous. The example below shows how the tritone C-F# can resolve in two different ways: “inward” to D-flat major (or minor), or “outward” to G major (or minor). The two possible resolution keys, D-flat and G, are themselves separated by a tritone. The tritone is so weird in this way that in early music it was considered diabolus in musica (“the Devil in the music”) and was off-limits when arranging liturgical music for a choir.

As the figure below shows, a number of WSS’s songs have a melody built around or prominently featuring a tritone. (In the examples below, for simplicity I’ve transposed all the song excerpts into C major so that the notes in the tritone are always C-F#, even though in the show the songs are sung in different keys.) The Act 2 curtain is musically notable because the final statement of the “Somewhere” theme has been playing, and (given the show’s key) the dominant harmony under that melody is an F# dominant seventh chord. Yet on the very last chord of the show, Bernstein introduces a regular C major triad (in the high woodwinds) against the F# in the bass (low strings)—a tritone. It leaves the show on an unsettling note, so to speak, and in my opinion is one of the best curtain buttons ever.

Less obviously, the main melodic figures of Tony’s first song, Something’s Coming, both start on F# even though the underlying chord is C—another tritone. And in Gee, Officer Krupke, the intro to the song (and to each verse), just before the vocals start, has a woodwind run-up that lands and sits on a high F# against the C harmony underneath—you get the idea.

Book

The book (script) by Arthur Laurents is amazingly short given how much action occurs in the show. There is startlingly little spoken dialogue, and every line serves multiple purposes (give background, move plot along, reveal something important about character or context), as is typical for Laurents.